Building flight

One St. Paul member built his own airplane from scratch. Another built a career from the seat of Navy P2Vs. Both share a love of the air.

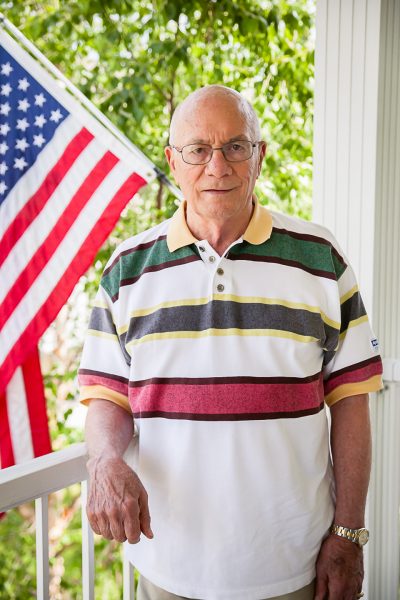

Richard Fidlar, retired Navy captain

As a student at Davenport High School, some of Richard Fidlar’s buddies decided to take the exam to qualify for a Navy ROTC scholarship. Richard, who grew up during WWII, went along. He took the test and earned one of two full-ride scholarships in the state of Iowa. With $50 a month in spending money, he enrolled in the civil engineering program at Iowa State University in the fall of 1953. It was during that time that his career as

a pilot became clear.

Richard spent the summers during college on what the Navy calls cruises. One in particular sparked his interest: his ROTC instructor wanted to get some flight time in, so he asked if anyone wanted to go up with him. Richard said yes. “That got the hook set,” Richard said.

What followed next was decades away from his hometown, working for the Navy, then for Rockwell Collins. Three years ago, he and his wife, Shirley, returned to Davenport and to St. Paul.

Richard and Shirley met in high school. He first noticed her while cruising around Davenport one night with a friend in his dad’s 1948 Kaiser. They married at St. Paul when he finished college. They were one of the first couples married in the new sanctuary of the time – now the Chapel.

Richard went to Florida and Texas for training. Then it was off to a squadron in Hawaii that deployed to Alaska. He and Shirley lived in Pennsylvania, Indiana, Virginia, New York, and New Jersey (that was for a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering at Princeton). Time internationally is on the list, too.

Richard and Shirley moved to most places together, raising their two children along the way. But sometimes, that was not possible. One example is when Richard served on the USS America during the Vietnam War. He was the communications officer for the carrier.

“I’d go weeks without hearing from him,” Shirley said. Communication was mostly all by mail (they numbered the letters to ensure they were reading in the right order), with an occasional call connected via ham radio. Even middle-of-the-night calls were so very welcome. While they were in Hawaii, phone calls home to Davenport cost $25 a minute.

All told, Richard flew 5,000 hours, 3,500 of which were as the pilot in command. Mostly he flew the P2V-5 and the P2V-7. It’s a long-range patrol plane that he flew to track Russian submarines and shipping activities in

the Pacific. The plane had a crew of 11. One of his favorite recollections as a pilot was during the flights of 10-11 hours that took off at night. “With the sun coming up, there’s nothing like having fried eggs, coffee,

and juice for breakfast,” he said.

One of the more harrowing incidents was when his plane was struck by lightning. One crew member was knocked unconscious, and the strike sent fireballs through the plane. Thankfully, no one was seriously injured or killed.

When Richard retired after 28 years in the Navy, he and Shirley returned to Iowa for a job at Rockwell Collins. He was a program manager for a project that developed avionics and weapons control systems for Army special operations aviation. After 12 years at Rockwell Collins, he retired from there. The couple spent 17 more years in Cedar Rapids before returning home.

Richard “thoroughly enjoyed” his career. His advice to young people considering a career as a military pilot?

“If they are serious about it, look into scholarships,” he said. And if they are not sure college is the right path, then look into one of the local programs, like Civil Air Patrol, to start the process of learning how to pilot an airplane.

One visual reminder of his time as a pilot is the model P2V he built himself. It hangs from his office ceiling.

Jim Smith, airplane builder

Inside Jim Smith’s hangar at the Davenport Municipal Airport, cold water and a seat await any visitor who stops by. The stories begin with the tale of the plane toward the back of the hangar.

It was built, not by kit, but by plans given to Jim by his wife Beverly early in their marriage for an anniversary gift. Each piece was purchased and installed by hand over many years, while Jim balanced work as training coordinator for the plumbing trade and raising a family, too.

Jim and Beverly met at the airport. She worked there. He stopped by the office for a variety of reasons. The two are about to celebrate the 53rd anniversary.

“I got it all ready, except for the engine, instruments, propeller,” he said. He waited for a damaged (but not too damaged) plane to come along for those particular parts. “Some people like to golf. Some people like to read books. I like to do things with my hands,” Jim said.

The first few times Jim flew the plane, he stayed close to the airport, checking for all sorts of things. Over the years, the plane took Jim and Beverly to Florida, Wisconsin, Colorado and “we’ve been around Iowa a lot,” he

said. Its name is Renegade II. The only downside of the plane is that not much luggage can fit inside. And, he and Beverly cannot sit next to each other while they fly.

That’s where his 1942 Waco VK5-7F comes in.

Jim had been on the lookout for a plane that would give the couple a chance to pack a bit more luggage and sit next to each other. He was on his way to an airplane show when Beverly gave the nod and said, “Why don’t you bring one home.”

The Smiths’ Waco is a rare aircraft, with just 21 built for the Civilian Pilot Training Program, an initiative of the U.S. government to increase the number of civilian pilots. It’s a round-engine plane, which means the pilot must crank the propeller a few times to get gas into all of the cylinders. Then, into the plane the pilot goes for a series of turning keys and pushing buttons. It slowly starts to rumble to life.

Jim started to learn to fly as a young adult. Today, it’s a hobby that takes him regularly to his hangar to tinker around with his beloved aircraft and the Model T automobile he rebuilt. The Model T is a bit slower than the planes, with a top speed of “55 miles an hour downhill with a tailwind.”

“It’s all about manipulating the wrench a little bit,” he said.